Collecting Comme, at the NGV International until July 26, 2020, reveals as much about the legendary designer Rei Kawakubo’s most passionate followers as it does about her relentlessly radical fashion collections. Janice Breen Burns meets the curator, and the collector, behind the exhibition.

(This feature first appeared in Nine media)

In 2017 Anna Wintour quipped that anyone headed to New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s newly launched Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garcons Costume Institute exhibition might be bamboozled by what they see. ‘‘If you’re not a fashion obsessive,’’ she said, ‘‘you’re going to be incredibly baffled.’’ Wintour knows her Kawakubo. Bafflement comes with the visionary Japanese designer’s avant garde fashion territory and in popular media it’s usually her kookiest collections that are pitched up for jolly ridicule.

The ragged black bagfrocks of her first forays into Paris in the early 1980s, for example, or the lumpy (literally) Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body collection of spring-summer 1997. Tips of a provocative iceberg. Never mind that Comme des Garcons ready-to-wear racked across the planet is wearable, albeit in an offbeat, intellectually intriguing way, it’s the loftiest flights of experiment shown on runways by Kawakubo and her stable of protegees (including the almost equally famous Junya Watanabe) that define genius for aficionados and draw potshots from the, let’s say, less enlightened.

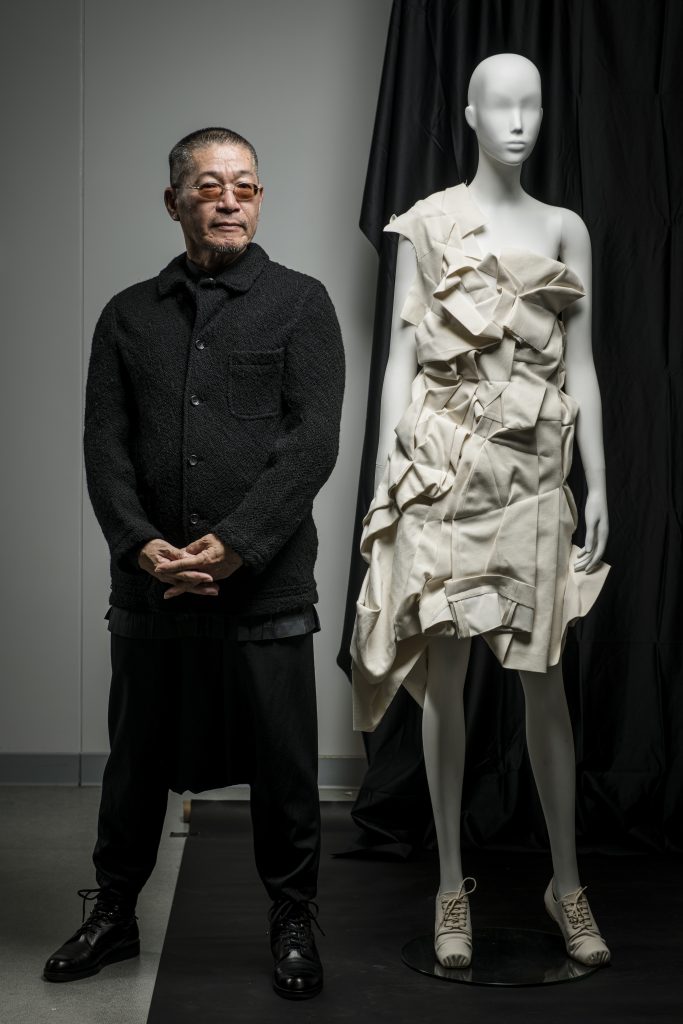

Takamasa Takahashi with mannequins from the Collecting Comme exhibition. Supplied by the National Gallery of Victoria.

Kawakubo herself is notoriously reclusive, communicates mostly by statements released for special occasions and does deep-dive interviews very rarely. But enough information has been harvested since 1969, when she first got Tokyoians pondering the purpose of fashion, to know she begins every creative project at zero. ‘‘(I’m) trying always to find something that didn’t exist, something new,’’ she told Business of Fashion’s Tim Blanks, one of the few journalists she’ll grant a deep-dive now and then.

From left, Junya Watanabe ensemble from 2006; Tao Kurihara dress, 2009; Rei Kawakubo dress, 2003-04. Supplied by National Gallery of Victoria, Collecting Comme exhibition.

To those who don’t get Kawakubo, she’s a madwoman churning out more weird stuff every season. To fashion’s more receptive souls, including many of its august journalists and academics, she’s a visionary genius, a goddess disruptor and bringer of progress. And in fact, the battle lines between the detractors and devotees are part of fashion’s evolutionary process.

Danielle Whitfield, curator of the NGV’s Collecting Comme exhibition, describes Kawakubo’s contribution best: ‘‘There’s shock, and then there’s change.’’ Collecting Comme illuminates how many of the designer’s visions, odd once, connected with a few mavericks, spread, and evolved into widely accepted fashion trends we now wear without thinking.

‘‘Part of the Comme legacy is the things we all take for granted,’’ Whitfield says. ‘‘The ubiquity of black for instance, or the fact that clothing can be distressed, can be asymmetrical, can be oversized. All of those things were radical and shocking when she introduced them, but they’re not now.’’

If we project back, suggests Whitfield, then forward, remembering what new fashions unnerved us once, but don’t now, and what unnerve us now, but may conceivably not in the future, we illuminate how Kawakubo’s work – and that of other radical designers – can worm its way into our lives.

Rei Kawakubo, playsuit and stockings. Supplied by the National Gallery of Victoria, Collecting Comme exhibition

‘‘I know people will look at [Kawakubo’s] jumper full of holes for instance and maybe say ‘that’s ridiculous!’,’’ Whitfield says. ‘‘Or, at the red cape from her Blood and Roses collection that extends two and a half metres out from the body and say ‘who’d wear that?’.’’ But it’s sobering to remember we wore crinolines once, and powdered wigs a metre high: the process of how fashion gets from there to here underpins Collecting Comme.

Whitfield sees collectors as empassioned conduits between a designer’s most radical ideas and, ultimately, wider acceptance. ‘‘[Kawakubo] actually questions the physical limitations of the body,’’ she says. ‘‘With a lot of her wearable objects, she challenges our Western canons of dressmaking, like perfect fit and what is beauty, and our ideas around a fashionable body.’’

Such radical concepts need empathetic first responders to gain traction among fashion consumers, and Kawakubo has them. She’s lured flocks of besotted followers and collectors since 1969, when she was a young arts and literature graduate/cum fashion stylist stitching visions under her fresh but soon-to-be-legendary Comme des Garcons label. Her first Tokyo boutique, opened in 1975, was catnip to a cult of uber-cool black-clad followers dubbed Kawakubo’s Crows by Japan’s pop press. Five decades on, they’re no longer called Crows but followers and collectors of Kawakubo. Her Comme des Garcons protegees – Watanabe, Fumito Ganryu, Junichi Abe, Chitose Abe, Tao Kurihara and Kei Ninomiya – have evolved and proliferated around the world. (The Comme des Garcons empire, including Kawakubo’s Dover Street Market retail concepts, reportedly turns over $320 million annually.)

Takamasa Takahashi has been collecting the work of Comme des Garcons since the 1980s. Picture: Eugene Hyland

‘‘There are two parallel narratives in this exhibition,’’ Whitfield says. ‘‘One is the curatorial story of Comme de Garcons and Kawakubo’s legacy: how and why she started in a very radical manner and 50 years later is just as radical. The other is the story of a collector with a particular connection that goes back to a time and place when he first encountered [Comme]. It’s a story about how our relationships to fashion are often about our own identity.’’

The story belongs to Takamasa Takahashi, living in Queensland since 1989 and a self-described ‘‘Comme tragic’’ who fell profoundly in love with Rei Kawakubo’s work when he spotted it in a magazine as a young man in Tokyo in 1976.

‘‘I had never seen images like this before,’’ Takahashi recalls. ‘‘Totally new, exciting! The photographs, so strong, models looking away from the camera, not fake, but focused on something internal. I felt [Kawakubo] is designing for us; she knows how I feel.’’

Comme arrived at a time when Japan’s conservatism was particularly frustrating for young Takahashi. ‘‘I hadn’t ever wanted to conform or be like every one else.’’ In his teens, he’d made his own self-expressive clothes, but it was a small rebellion.

Kawakubo triggered his epiphany, turned him into a connoisseur and collector. Although the magazine featured only her women’s collection (she didn’t launch Comme Homme until 1978) he was still thrilled. ‘‘She created very baggy, sizeless, shapeless clothes, so it didn’t matter.’’

Later, between 1981 and 1983, when Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto showed their collections in Paris to several seasons of slowly thawing front rows, those same bagged black silhouettes with their ragged, assymetric edges, would revolutionise – Japanise – womenswear across the planet.

But for now, a young man’s identity was puffing up and bonding with Comme. ‘‘Thinking back,’’ Takahashi says, laughing, ‘‘I was probably the only man in Tokyo walking down the street wearing the women’s collection!’’

Rei Kawakubo, overdress and dress 1995, from the Transcending Gender collection. Supplied: National Gallery of Victoria, Collecting Comme exhibition.