It seems there’s no middle ground being expounded for the future of AI: it’s either bloody marvellous or it’s apocalyptic. In real-time reality though, down among the thinkers, dreamers, artists and story-tellers of the fashion industry, AI tech is a thrilling playground, a laboratory, an philosophy gym and a vast unknown they’ve only just begun to learn. Janice Breen Burns asked six fashion industry creatives where they’re at with AI, and where they’re heading. (This story first appeared in Nine Media’s The Age and Sydney Morning Herald Spectrum arts/culture magazine.)

Most experiments with Artificial Intelligence begin with a bit of faffing on a phone app. AI Arta or Wonder, for example. Tap in any crazy thing: “Old woman with tattoos nose-ring puffy rainbow hair and matching poodle…” And there she is. Instant gobsmackery delivered into the palm of your hand.

These are your AI “prompts”, instructing the app to target-harvest your concept from millions, possibly billions, of images that it’s already “scraped” from the internet. It scoops them according to caption (this is an important point) and mashes them into an idea of your idea. And there he is, alien angel boy. Amazing. Admittedly, a party-trick that quickly wears thin but, still, amazing.

It’s a short leap to imagine this crazy amazing AI thing slipping like a shiny new set of tools into the professional lives of visual creatives. Designers and photographers in the fashion industry for example.

And so it has. Despite multiplying copyright court battles and increasingly dire predictions, of course it has. Who wouldn’t plunge up to their moral compass into a bucket full of such easy-peasily achievable miracles? In fact, in less than a year since AI apps infested phones and computers across the planet, the six creatives you’ll meet here have pushed their professional practices way beyond party tricks into the seed phase of a new fashion industry that, by all their accounts, brings little shocks – pleasant and not-so-pleasant – with every new day.

Early AI adopter, Spanish designer Ines Aguilar of slow fashion brand La Casita de Wendy, for example, taught herself complex AI prompts and conjured 10 dreamy couture outfits that sold out (on pre-order) before their supernaturally lush patterns and piled-on floral embroideries were even cut and stitched into existence.

Renowned Melbourne based photographer Philip Castle is another early AI adopter and, in one of those small, pleasantly shocking revelations common among creatives, says he “accidentally” designed a pod of vintage-style floral dresses – quite lovely and as viable for market as any if he can only source similar fabrics and get them made – while working on a folio of hybrid fashion images.

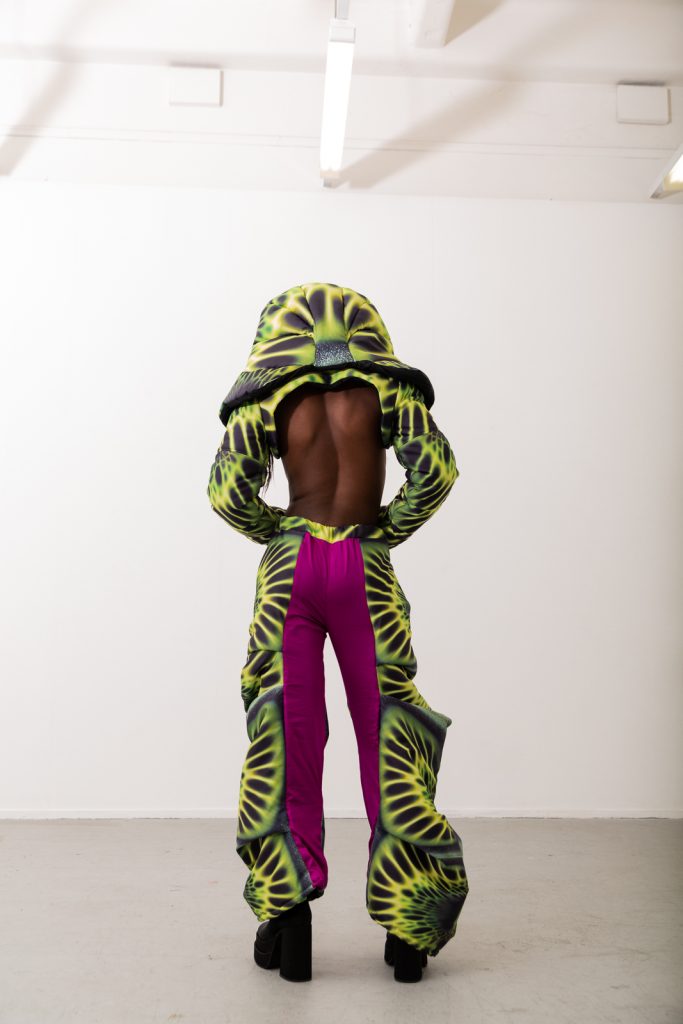

In the industry’s fresh “phygital” (physical/digital) space, London based academic and hybrid designer Oscar Keene is also inventing his own AI tests, composing prompts to “ask” one algorithm (ChatGPT) how best to prompt another algorithm (MidJourney) to create his design concepts.

In fashion education it’s taken just a few thrilling months for AI to become a crazy-good teaching tool too, according to LCI Melbourne academic and brand consultant Todd Heggie. He says it’s accelerated fashion course learning by several weeks and – bonus – freed more precious time for students to practice and apply finer couture crafts such as French embroidery, crochet and other embellishments to their collections.

AI’s most wondrous results however, are in fashion’s story-telling realm and these pepper social media platforms. Punch “AI fashion” into any search portal and thousands of generative and hybrid (a mix of the photographer’s work smashed into new visual concepts with AI-prompts) images of unlikely models wearing unlikely designs in unlikely locations erupt on screen.

Milan based Italian photographer, Eugenio Marangiu’s often elderly models, heavily tattoo-ed or with ice-cream clouds of multi-coloured hair and weirdly wonderful fairy-tale wardrobes, often bubble up among the first. “I’m still trying to understand (AI’s) potential,” says Marongiu who also posts under the Instagram pseudonym Katsukokoiso.ai. He is one of AI’s busiest novices with a brace of brand collaborations, media coverage and a group exhibition in China already under his belt. “I haven’t stopped experimenting, studying, creating…”

Melbourne fashion documentary photographer Liz Sunshine plays with a similar aesthetic to Marongiu’s weirdly perfect, smooth-as-a-sucked-lozenge AI images, but she interprets it purposefully, as a radical re-jigging of beauty ideals for elderly women. Her AI hybrid posts have also clocked up millions of views on social media.

Sunshine, Aguilar, Marangiu, Castle, Keene, Heggie and his students could be described as fashion’s self-taught pioneers, still learning the which why and how of prompts to tap into AI systems – algorithms – with names such as Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, DALL-E.

“It’s been a trip,” says Castle. “I used to fantasise about this kind of thing, being able to blend this face with this face, add a dash of this and a dash of that and AI does it, it’s incredible.”

He’s run increasingly meticulous prompting experiments with San Fransisco based MidJourney, one of the most popular AI systems, ostensibly developed for artists and recognisable for its painterly, Wes-Anderson-ish aesthetic.

In a second, even more complex process, Castle then uploads his low-resolution MidJourney fashion images into a programme such as Topaz Gigapixel AI. And with slides and dials and strings of even fussier prompts, he refines these until the striations on a AI model’s lips and the fuzz on her cheeks is discernible in a final high resolution picture.

He’s conjured a folio of ethereally beautiful new fashion portraits this way, without hiring a single model or switching on a single studio light. He’s also, incidentally, re-booted a dormant chunk of his archive, a treatise on American culture he never got around to finishing in the 1990s, into a contemporary exhibition project by uploading the images and mashing original landscapes and AI generated portraits into visually evocative new hybrid pictures.

“It’s kind of like surfing,” Castle says of his typically short but epic AI adventure so far; “Like riding a beast but there’s also a substantial random factor involved…”

Although AI technology has been around in evolving iterations for centuries, its first official transactable artwork, reportedly sold less than five years ago, is an evocative indicator of its galloping recent evolution. Portrait de Edmond de Belamy was prompted into existence by French artist collective Obvious in an algorithm trained on a dataset of 15,000 existing portraits. It sold for $US432,000 at a Christies auction in 2018 and has been quoted like a contextual muse ever since, its wobbly, blurred features compared like relics to the artfully perfect works that virtually any amateur with a mind to can cook up in her iPhone these days.

“It’s all in the prompts,” says Castle. “You have to be able to describe what you want and, at a certain point you’ll want to upgrade (to a professional subscription in the AI programme) and go into stealth mode so other people can’t see your prompts….”

Creatives habitually refer to their way with prompts as recipes or formulas, or “X” factors that, in a pre-AI universe, might have defined Crystobel Balenciaga’s Balenciaga-esque-ness or Toni Maticevski’s Maticevski-esque-ness.

“If you don’t give AI the right recipe it’s not going to bake a good cake,” says Heggie. He cites the complicated case study of emerging designer Mathilda Sinagra’s fashion project as an example. Her idea, to use MidJourney and a blast of lateral thinking to develop garments inspired by the exoskeletons of extinct insects at first went awry. “I’m a staunch believer that to generate new, original and interesting design outcomes you shouldn’t reference fashion in any way,” Heggie explains. “You should start by building a concept that’s external from fashion..when you get closest to what you want, I tell students to start drawing over that, start dissecting the elements of the AI…”

Hence, the insects. Sinagra quickly realised however, that prompting with the characteristics of exoskeletons’ furry crunchy bits didn’t resolve AI images anything near as dynamically or colourfully as her off-beat fashion concept.

Heggie recalls Sinagra’s next puzzle-solving process: “She said, ‘ok, why don’t we put in (prompts) for an iris from an eye, and a lime, because they’re the shapes and colours we want’. So we did. We put in images of eyes and sliced limes and the AI created all these amazing print concepts, we picked one, sent it off, scanned in the (garment) patterns, digitally aligned them and (Sinagra) cut and made them.” Eyes, limes and insect exoskeletons fused perfectly into a remarkable AI hybrid fashion concept.

It’s predicted similarly original strings of carefully targeted, meaningful and complex prompts will eventually recognised legally in the realm of Intellectual Property. The idea is already being tested. In the US, there are also visionary companies paying a fresh-shucked breed of non-technical professionals six figure salaries to be their prompt engineers. Prompts are that precious.

“I’m of the opinion that prompts, especially in cases of professional/artistic use, should remain secret,” says Eugenio Marangiu. “It’s like a chef revealing his secret recipe or a photographer giving away the raw files of his shoots…”

He prompts his own AI images into existence with the same intuitive, artistic beat and process of his real-world work. “I move exactly as for a photographic shoot,” Marangiu says, “But everything is at the written and mental level: the type of models, the location, lighting, outfits, makeup and hairstyle…A single word placed in the wrong spot can change everything…”

Creatives liken it to re-learning your own language. “Initially my prompts were simple; ten words,” says Sunshine. “But I became more precise about what I wanted to create; I found the words to describe a scene to a deeper degree, sometimes one hundred or so words…imagining women I would photograph in real life. I enjoyed seeing each subject’s story unfold…Simple details like skirts wrinkled from sitting or a woman with lumps and bumps make the images feel more real…”

Sunshine’s experiments have rocketed on social media. One image clocked more than 16 million views. “I’ve been using AI in all its forms for many years (but) in photography it feels new,” she says,”Creating images as a collaboration between imagination, bots and words instead of cameras and light.”

She’s sped up her art processes and – another on of those happy AI accidents – plunged into a book project that virtually opens a new cultural gateway and wouldn’t have been viable even a year ago. “I’m self publishing a book that questions style as we age and presents a series of AI images that celebrate the visual qualities of aging,” she explains. “I’ve always found older people beautiful; their grey hair and deep lines tell the story of life….yet both myself and the women around me feel differently, we feel an urgency to cover greys and anti-age at all costs. I hope this book offers a different narrative to the one that’s often hero’ed online..”

In a month Sunshine created an astonishing 6,500 base AI images for the book and edited them down to an exceptional 200. “That’s a lot less time that it may have taken me to find 200 subjects that met my brief and capture them in the real world…”

There’s only one category of fashion miracles yet to be mastered by AI and, Todd Heggie hopes, as machine learning enables AI algorithms to accelerate their own evolution, it might be possible in a few years, if not months. “Tech packs and spec sheets,” he laughs. “I think AI has the same disdain for that as we do.”

The laborious work of converting an on-screen concept into patterns and production instructions is simply an algorithm too far for AI in fashion right now.

Even Ines Aguilar’s marvellous “Artisanal Intelligence” couture collection is rare for its real-life outcomes. “We designed the collection with a specific colour palette in mind,” she says, “Along with the materials, embroideries, everything.” Real-life fabrics, yarns, even crafted details, in other words, were pre-loaded into her prompts.

Accessible AI is such a young revolution, fast evolving, fraught with unknowables and predictions both glowing and apocalyptic. Arguments are multiplying around the morality of AI algorithms that have “scraped” hundreds of millions of existing images from the internet, all without permission, many – possibly even most – protected by copyright.

Tap in a prompt that includes “in the style of” a particular artist or photographer, as some fashion creatives do, and the resulting AI image’s originality is automatically arguable. Definitions of “fair use” are increasingly being tested in courts by creatives worried their oeuvre is being hollowed out. As AI evolves, so does unease, despite assurance that algorithms skim and mash, they don’t replicate unless specifically prompted to.

“I do feel conflicted by it,” says Oscar Keene. “When I started I used prompts like “inspired by” and then thought; is this not plagiarism?”

The integrity and originality of his own work is a constant focus. “I love designing and when I share my AI work with other people their response is, ‘yes, it’s pretty, but it doesn’t have that thing, that point of view that you have. I think my point of view is diluted when it becomes part of AI.”

Keene continues to experiment but is ever vigilant, intellectually wary as AI evolves. “Sometimes I think when I’m using it, “Am I facilitating my own obsolescence?” I think it’s a great equaliser; people that aren’t trained in design are able to execute these creative visions… its a good starting point, gets the ball rolling on the design process. I’ve thought it would have been good when I was (studying design at RMIT) in first or second year but now..it’s a play tool. The more I’m interacting with it the less meaningful it is to what I want to do, to make designs that, when you wear them it means something to you…”