After a hundred years Gabrielle’s radical chic is still modern womenswear’s evocative backstory.

Words by Janice Breen Burns (Story first appeared in The Saturday Age) Main photograph (above) from “Paris Madness”, the evocative series shot for Chanel in the 1990s by the masterful Philip Castle, available to buy as prints on The Block Shop.

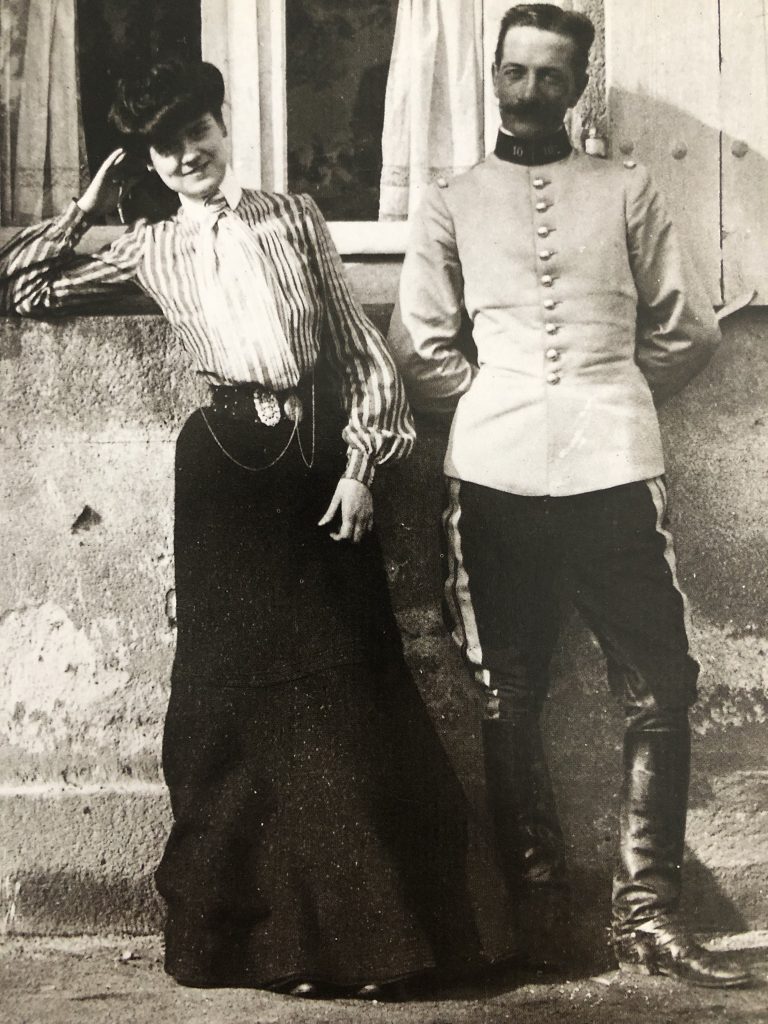

Even before she was Coco, Gabrielle Chanel was pretty cool. There’s a photograph of her aged 20 in 1903, fresh from convent school and now clerking – her first proper job – in a chic hosiery store in Moulins. She’s smiling a quizzical half-smile, wearing a strikingly striped gypsy-sleeved blouse with a stiff, Karl-Lagerfeld-esque collar (yes, ironic) and watch-chains loosely looped, caught into the filigree buckles of her tightly belted waistline. Tres originale. Tres moderne.

This was long before she’d flipped women’s fashion out of centuries of turkey-truss corsets into the liberating slip of soft fabrics and slumped silhouettes, long before portraits of her as the stunningly chic maven proliferated and already she’s got that look: “This is me; take it or leave it.”

Not long after this photo, the very witty, terribly clever young flirt Gabrielle would give nightclub singing a crack and the nickname “Coco”, after a couple of songs in her repertoire, would stick.

Later still, she’d draw a veil over her socially iffy origins; her peasant maman who died young, her peddlar papa who abandoned her, aged 12, to a convent orphanage. (And an equally forlorn bunch of sisters and/or brothers, depending where you dip into the vast muddle of Chanel truths and myths still blossoming since her death in 1971.)Finally, still in her 20s, the young Gabrielle would swim up and swan through French society’s rigid class barriers – a rare exotic among the aristocrats, celebrated artists and writers and wealthy young guns. She’d be buoyed by her natural business acumen, a succession of generous high-born lovers, and a provocatively modern arsenal of millinery and dress designs to which fashionable women, knowing an elegant answer to their secret wish lists when they saw one, flocked like moths to flame.

That’s Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel nutshelled and quite enough personal history, merci beaucoup, for Miren Arzalluz, director of Paris’ Palais Galliera and co-curator of Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto, on at the National Gallery of Victoria until April. “We avoided to go deep into her private life,” Arzalluz says, faintly scolding, via Zoom from Paris, “because we wanted to concentrate on her work.”

Quite rightly, too. Arzalluz wanted crystalline focus on why Gabrielle Chanel (notice, she even dropped the playful “Coco” in the exhibition title) is one of, if not THE, most seriously important people in fashion. Ever.

“It’s clear because her influence is very present in fashion still today,” says Arzalluz. “One of the things we’re trying to show is that timelessness, the modernity of her work, so strong you could see many dresses presented in a catwalk today.”

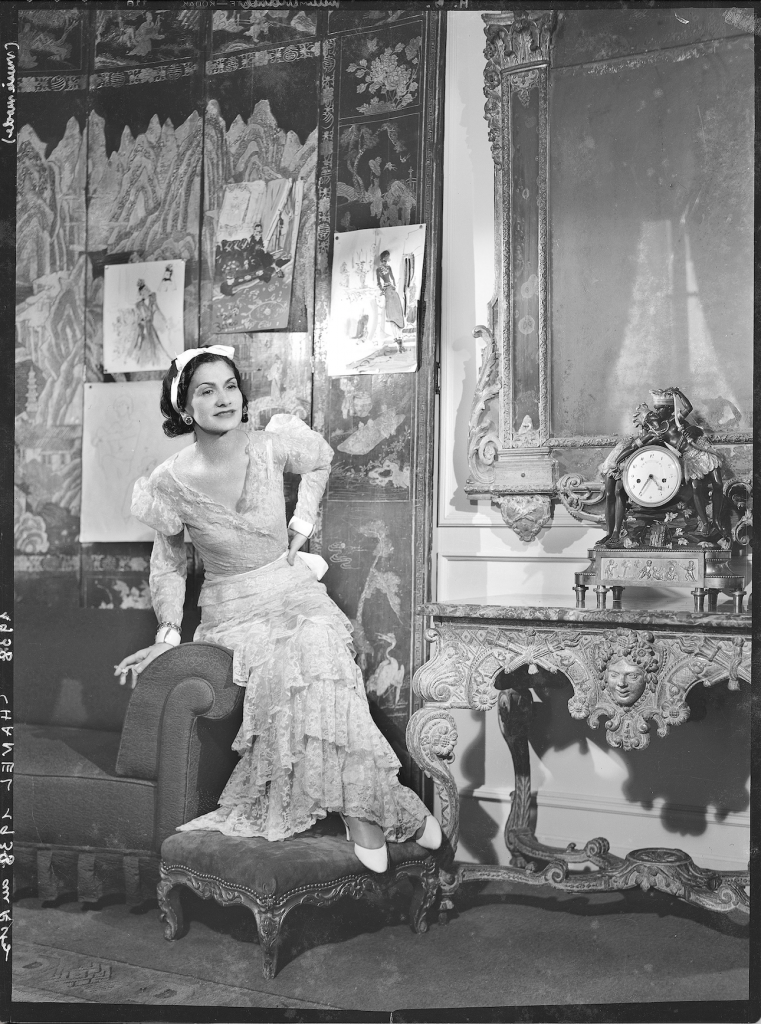

“We’re trying to show … the modernity of her work,” says Miren Arzalluz of the NGV’s Chanel exhibition. She did however, salt an earlier iteration of the exhibition at Palais Galliera with portraits of the imperiously sophisticated Chanel so that visitors can at least eyeball the legend, get a sense of her as the striking fashion influencer she was, “the embodiment of her own style”, but still focus on Chanel the designer, undistracted by the sort of superfluous personal side-tracks: “daughter of …“, “lover of …” that so often detract from women’s achievements.

So here is the advice: prepare to lean in to the glazed exhibits when you visit, focus on the exquisitry of Chanel’s couture (a thicket of 1930s lace and silk tulle gowns is reportedly particularly swoon-worthy) or the glittering OTT elegance of her commissioned semi-precious jewellery, but also, hone in on the simpler pieces.

They too reveal Chanel the maverick, Chanel the original thinker, the problem solver, the blast of feminine common sense at a time when fashionable women literally hobbled in couturier Paul Poiret’s skirts, drew shallow breaths in Charles Frederick Worth’s rib-crushing whalebone corsets. “Natural was the opposite of fashionable,” Arzalluz explains of 19th and early 20th century modes. “To be comfortable was not important.”

But it was to Chanel. “Before she was a designer she created clothes for herself,” Arzalluz says. “And she was always trying to understand what women needed and wanted.”

The stupider the mode, the more inventive and sensible young Gabrielle’s designs. She was notorious among her smart-and-arty mates for raiding her boyfriends’ wardrobes, adapting their simpler, tailored jackets, shirts and coats to an aesthetic that, applied to women’s wear, would soften and de-emphasise waists, breasts and hips, and eventually become her iconic couturiere style.

Turning her minor revolution into a business was inevitable, but Chanel started with hats. Her very first business, as a “modiste” or milliner (and yes, seed-funded by her lover at the time, celebrated horse trainer Etienne Balsan), offered simple, chic alternatives to the elaborate multiple-kilo concoctions of feathers, flowers and what-all geegaws women wore at the time on their heads. Chanel was aghast at their absurdity. “Grotesque,” she once sneered. “How could a brain function normally under all that?”

Her own millinery was unfussy, sparsely adorned, often with a swooped, deeply tilted brim. Around this time, 1910 to 1912, she also made prophetic adaptations to a boater style worn by men including Balsan. She wore one herself, for its practicality, wind-resistance and simple chic. Her trend caught on. A century later, versions of the Chanel boater and its Chanel-esque imitators still pock the most fashionable racetrack and polo crowds.

Chanel hung out her first official shingle as a couturiere in 1913 (yep, bankrolled again by another lover, Arthur “Boy” Capel) in the fashionable seaside town of Deauville. In its daily parade of stuffily coiffed and corseted women she saw an urgent need for fashions that flexed and – quelle horreur – could be paddled in, in the shallows, or even swum in.

Chanel snaffled some knits from Capel’s wardrobe for inspiration. She ran up voluminously modest swim bloomers and dress sets, a comfortable sailor-style blouse, cardigan-like jackets with pockets and other shockingly soft garments. She used a knitted jersey sourced from the French mill Rodier and a Tricot fabric once reserved to make men’s undies and, voila, the first ever pod of practical women’s fashion that could only be described as “sportswear” was on the market.

Fashion would never be the same. And neither would Chanel. By now she was in her early 30s. As war exploded across Europe, women responded hungrily to the liberating simplicity of her couture, now sold in boutiques at Deauville, Biarritz and by 1918 on Rue Cambon, Paris. Her workforce had swelled to more than 300 dressmakers and assistants. She had paid her boyfriend back every franc and caught the eye of fashion editors across Europe and the United States. She was a mega-influencer for her own brand and, by 1921, indulged a crazy notion to develop her own perfume and a range of cosmetics so small they could be popped in a purse. An icon hatching icons.

“We are all very familiar with her icons,” says Arzalluz, “her [tweed] suits from the 1950s and 1960s, the handbags of 1955, the two-tone shoes, the simplest black dresses with a huge accumulation of jewels, but what is fascinating is to see how all these codes and all these principles were established by her from these very early years. She had such a clear vision of fashion which combined freedom of movement and freedom in general with chic and elegance …”

At the NGV, senior curator of fashion and textiles Danielle Whitfield supervised the installation of Arzalluz’ vision of Chanel’s legacy still pulsing through fashion. “You’ll see how Chanel established the principles by which we dress today,” Whitfield says. “One of her biggest legacies, the popularisation of the little black dress; if we look at fashion typology, that has been one of the longest-lasting symbols of modernity …”

Chanel shifted fashion’s emphasis from male gaze to female freedom. “She changed that relationship between the garment and the body,” Whitfield says, “dressing the female form in a different way, liberating femininity.”

The suffragettes must have loved her. Chanel’s fleshy fabrics and draped silhouettes triggered howls of protest from male editorialists – Marcel Proust among them – lamenting this new “absence” of breasts, waists and hips. Women responded with deaf ears. “Chanel wasn’t a feminist,” Arzallus says. “She never talked in those terms, though her life is an example of a woman who fought for her own independence and freedom through fashion.”

Soon after World War II, when Christian Dior proposed the return of figure-sculpting formwear for his radical “New Look” collection, Chanel’s protests carried a hint of feminist politics. “When she comes out of retirement in the mid ’50s she really hates the New Look,” Whitfield says. “She called it ‘upholstered’ and her answer was to go back to the ideas she had at the beginning of her career.”

Chanel’s years of quiet retirement in Switzerland following rumours of an affair with a German diplomat in occupied Paris appear to have sharpened her resolve around comfort and elegance.

“So she introduces a supple, subtly tailored suit with pockets and without interfacing and without shoulder pads or darts or a collar,” says Whitfield, admiringly. “It was like the cardigan jacket of the ’20s reinvented but in these specially woven tweeds. It was about giving women this lightweight outfit they could move easily in and it became, not quite the uniform for everyday working women [she intended] but, certainly for the upper class and society woman, these suits for daywear, and in woven metallics for evening, that were utilitarian but such an elegant harmony of proportions …”

The exhibition’s 100-odd garments and 80 items of jewellery, cosmetics and perfumes were mostly sourced by Arzalluz from Chanel’s remarkable archive, private collectors around the world and the NGV’s own permanent collection.

Whitfield suggests we watch for technical brilliance, radical concepts and unexpected loveliness. She says every exhibit personifies its period, including a gobsmackingly gorgeous bulls-blood red velvet and marabou feather cape dated 1924-26 and recently acquired by the NGV for its permanent fashion collection.

“It typifies the way Chanel unified decoration and material to give this sense of restrained luxury,” Whitfield says. “It’s such a beautiful work, with the softness of the velvet and feathers and richness of that red. She was well known for using this particular shade, though we associate Chanel more often with black.”

The cape’s place in Chanel’s oeuvre and context in her modus operandi are as clear as every exhibit’s in the show. “Every design innovation is looked at for how it played out [in her designs],” Whitfield says, “in the great suits of the 1920s, the jersey daywear, little black dresses, the romantic fashions of the 1930s, including those beautiful lace and tulle evening dresses, so technically complex in their construction, and the familiar tweed suits of the 1950s and 1960s …”

There are portraits and clips too, including fascinating footage of Chanel’s final show in Paris in 1971, and an Aladdin’s trove of the jewellery Chanel commissioned from the most exalted designers of their time. “So rich and opulent,” Whitfield says of the room. “It references her mantra of the juxtaposition of simplified elegance in clothing with this ostentatious, more-is-more aesthetic of the costume jewellery.” All elements of an unmissable exhibition showcasing the remarkable mechanics of Chanel’s genius and the impact she has still on most women’s wardrobes.