A new generation of bolshy girls has smashed thousand-year-old beauty standards to smithereens. Who’s beautiful now? Their answer; “fuck those old-man rules“, I am!

This feature first appeared in The Saturday Age arts and culture section Spectrum.

It’s a wintry Wednesday morning in North Melbourne and model manager Chelsea Bonner is uncharacteristically elated. Her casting call for Melbourne Fashion Week’s “real people” runway show is going off, a noisy couple of hundred wannabe models already queueing to walk for judges who were picked, she says, “to represent as many different kinds of humanity as we could fit on a panel”.

Chelsea Bonner

Bonner watches the wannabes walk; shyly and awkwardly, or like practised amateurs, or striding off, hip swinging supermodels-in-the-bud, across the intimidating expanse of slippery floor.

There’s a lot of classically pretty, slim, young, Caucasian model-types among them, but Bonner’s heart sings especially for the rest: tall, short, fleshy, skinny, all shapes and ages and a broad palette of complexions, gender orientations, races and physical abilities. All manner of humanity. This ain’t your average model call.

No, this, if there’s prophecy in the waves of change crashing across fashion right now, is early proof our ideal standard of beauty is splintering into a zillion bits. Precisely what will replace it isn’t clear, but it’s beginning to look a lot like you and me.

“You know those blonde and brunette versions of classically pretty 5’9″ Caucasian beach girl models?” asks Matthew Anderson, head of Chadwick, a long-time supplier of models and ambassadors to Melbourne Fashion Week. “Well, they’re always going to find a job in modelling but it’s the interesting ones who are in the majority now. It’s a change in modelling that’s happening fast; until just two or three years ago, those [classics] made up 70 per cent of [Chadwicks], now they only make up about 30 per cent.”

Yep, interesting is the new black. Diversity and body positivity the new pinks. And the shockingly fast changes to our concepts of ideal beauty are being accelerated by Millennials and Generation Zs, the most vocal collection of young women in history, says Jenni Middleton, beauty director with trend forecast and analytics company WGSN. “They’re noisy, they’re articulate, and they’ve got social media,” she says.

They’re also easily peeved. “They don’t want to be dictated to. They want to be their own heroes. They’re about female empowerment and diversity and reality and they’re going to call it out if they sense something’s not quite right.”

Millennials and Gen Zs fire off disruptive little skirmishes across social media every day, triggering shocks that question, criticise and ultimately tap cracks into what they see as beauty’s antiquated status quo.

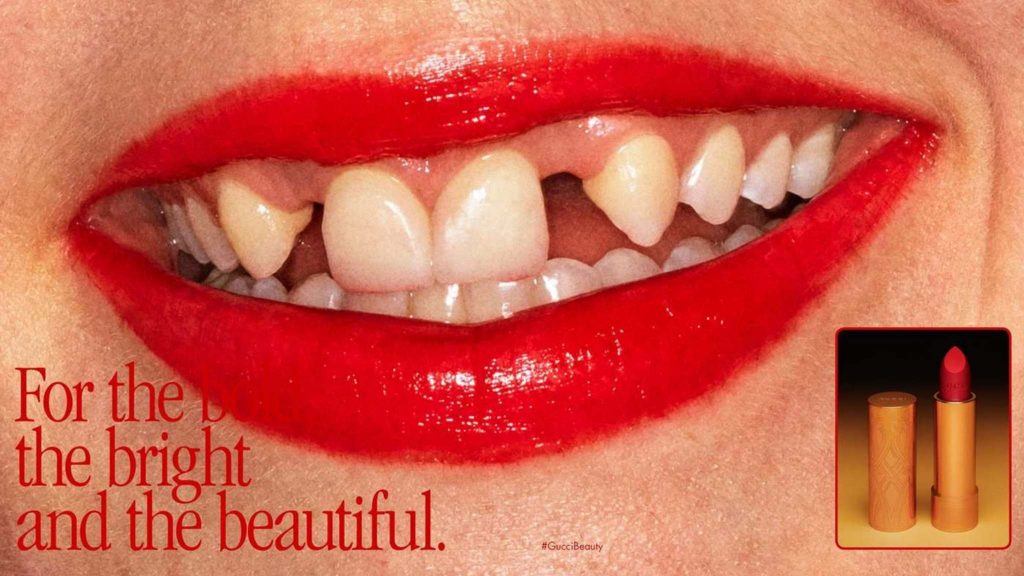

The fallout from Gucci’s now infamous “crooked teeth” Instagram lipstick ad, for example, was a spectacular example earlier this year. Photographer Mike Parr’s untouched picture of musician Dani Miller’s crooked, gap-toothed smile set off nearly 21,000 reactions. “This will definitely not motivate anyone to buy this f—ing lipstick!” was typical. Others posted green-faced vomiting emojis.

Gucci designer Alessandro Michele weighed in, explaining his idea for the campaign as “close to reality with a humanised point of view, however seemingly strange. But the strangeness is human, so it’s beautiful.”He needn’t have. There were enough delighted backlashers to prove Gucci’s risk was very much in sync with the zeitgeist: “Real faces! Beautiful!”; “I feel it says you are beautiful, whatever your form…”

It’s squabbles like these that are chipping away at fashion’s classic beauty standard. Before Gucci it was freckles in a Zara campaign, curvy sportswear mannequins in a Nike store, the relevance of Kim Kardashian’s backside and the myriad models with scars, wrinkles, skin conditions and disabilities increasingly cast for fashion week runways from Melbourne to Milan.

Jamaican-Canadian model Winnie Harlow is a pin-up example of what feels like the impending new world order. Six million Instagram followers, a full book of runways, campaigns and covers every season, yet Harlow’s severe vitiligo, a rare condition that bleaches random patches of her otherwise dark complexion, would have excluded her from any significant public exposure, let alone international modelling, even five years ago. As it is, in the realm of social media, her vitiligo resides somewhere between inspirational and of no consequence at all.

According to Middleton, these waves of change in fashion and social media are having the most profound effect at the frontline of popular culture, in marketing and advertising. “Brands are recognising they’re ripe for disruption and they’re clamouring to capture the zeitgeist,” she says. “They need to find the most diverse faces, body types, voices, to reach this generation [whose] natural expectation is to be welcomed, understood and accepted. If they have to ask ‘What about me? What about my skin? My hair, my [hijab] or what about my African or Asian identity, my gender identity?’ then, [the brand] is missing the trend.”

Brands’ trickiest task, however, is letting go of a notion supported by eons of human history. It’s an ideal beauty standard, applied mostly to women, that’s been propped up by patriarchies since the dawn of time and mostly accepted with resignation.

There are, however, some memorable exceptions. Simone de Beauvoir bitched about it in The Second Sex in 1949. “It’s not the mythical thought that is wrong,” she wrote of what she called the “false identity” expected of “truly feminine” women, “but the flesh and blood women who are wrong.”

Academic Marianne Thesander also took a crack in her 1997 book The Feminine Ideal, complaining that society expected women’s “natural bodies” to be “reformed into an acceptable cultural image of femininity” to which most had “very little access”.

Strateas Carlucci at Melbourne Fashion Week 2019

Photo: Audrey Michael

The late beauty entrepreneur Dame Anita Roddick also had a go in her campaign for The Body Shop retail chain the same year, saying: “There are three billion women who don’t look like supermodels, and only eight who do.”

The ideal beauty standard however, barely wobbled until recently. Most women’s body shapes and weights, ages, races, complexions, physical abilities, even hair colours and textures didn’t make the average casting call. And it’s hurt.

“When no one has hair that looks like yours you start to ask questions,” wrote one young woman of African heritage on the Galore Magazine website. “What’s wrong with mine? How do I tame it? Why can’t I just have normal hair?”

Women and girls have dealt with such “imperfections” for eons by covering them up, or cutting them off.

“Ideal is never something effortlessly obtained,” says Lauren Rosewarne, senior lecturer at the University of Melbourne and author of 10 books on gender, sexuality and the media. “Ideal is a product of an industry that wants to sell us on the idea that our bodies are imperfect.”

Whyte Studion modelled at Melbourne Fashion Week’s Highrise Runway.

Photo: Audrey Michael

Power and money and the men who wield them, she says, are key drivers in the evolution of female beauty standards. “But it’s also important to recognise the story is more complicated than that,” she says. “The rounded female bodies associated with artists like Rubens, for example, are often looked at as reflecting a time, early 1600s, when fleshier female bodies were in fashion. Fleshiness wasn’t simply desirable on its own as an aesthetic statement, but for what it represented: wealth, excess, opulence. “When scarcity is a genuine concern,” Rosewarne adds, “we like rounded bodies that signify what we don’t have. When we have plenty, when obesity is a social concern, we have the luxury of idealising thinner bodies.”

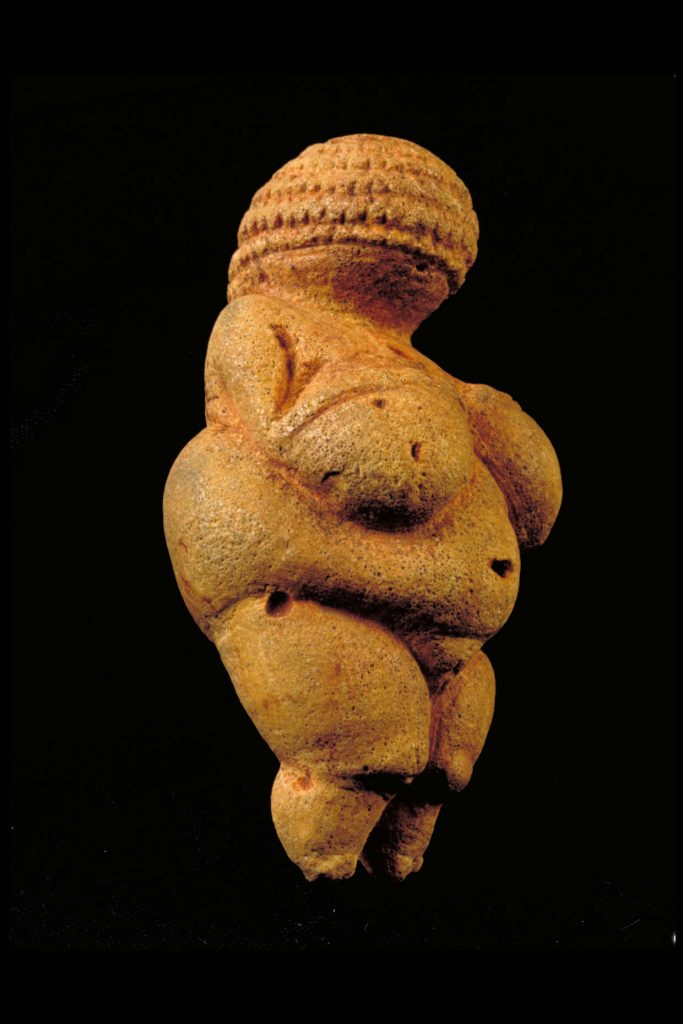

She tracks the historic arc of idealised beauty back to between 22,000 and 24,000 years BC, to the sculpture of a lumpy, large-breasted woman known as the Venus of Willendorf. Fertility was particularly sexy back then. “(It’s) often used to showcase the sharp difference to bodies lauded today,” Rosewarne says.

In fact, the squat little Venus sits in spectacular contrast to both prongs of beauty’s contemporary standard: the trim, young, shapely, full-breasted Caucasian ideal of popular culture, and the tall, boyishly slim, near-breastless beauty of fashion’s average runway model. And Rosewarne says it’s in this latter arena that ideals now appear to be loosening and the flutter of purpose to represent something more “real” than “ideal” is being felt. “We’re getting a much more complicated picture of ‘ideal’ now,” she says. “One that is substantially more complex than the pages of Vogue might indicate.”

Back at Chelsea Bonner’s noisy casting call for Melbourne Fashion Week, that truth thrums, a cheery buzz around the venue. Ten, or even five, years ago, this would be a tokenistic nod to fashion’s patchy planet-wide revolt against its own impossible standards. Now, who knows? This kind of search for humanity’s “most inspiring”, “most interesting” and “most photogenic” (“Models still have to be photogenic,” says Bonner) instead of its prettiest young striplings, could feasibly become routine. Imagine that.

“I’ve been spruiking this for so many years,” Bonner says passionately. “[Fashion] should be inclusive and diverse and count every human – every kind of human – as important.”

Adut Akech

Melbourne Fashion Week’s two principal ambassadors, Adut Akech and Jess Quinn, are proof the tide is turning.”Growing up, I didn’t always feel represented by the fashion industry and mainstream media,’’ says Akech, 19, now a star among several South Sudanese Australian models swept up in fashion’s ‘‘New Real’’ era. Akech spoke out this week after Who magazine ran an interview with her accompanied by a photograph of another model; in a statement on her Instagram account, she said: ‘‘I feel like my entire race has been disrespected’’.

Jess Quinn

Akech is based in New York, walks for most major brands, appears on glossy covers and in major campaigns, counts diversity pioneer and supermodel Naomi Campbell among her nearest and dearest and has a whopping half a million Instagram followers. So confusing her with another model points to some distance still to be travelled on the diversity road.

Her fellow fashion week ambassador, activist and lobbyist for body positivity, Jess Quinn, 26, is also deeply invested in a more diverse new world order. ‘‘Even three years ago this idea of seeing different as normal was just so far-fetched,’’ she says. ‘‘Now I have two modelling agencies; one here and one in LA.’’

Quinn lost her right leg to cancer at the age of nine. “That was my ‘normal’ until I was heading into my teens,” she says. “Then all my friends were starting to get boyfriends and wear mini skirts … I think it was the lowest point of my life.” Quinn recognised a standard of beauty was being imposed that she couldn’t dream of reaching. “I had to take control of what I could.” She became one of the most vocal and articulate young women of her generation, competed on New Zealand’s Dancing with the Stars to prove her athleticism, and accumulated 200,000 highly engaged Instagram followers. “I think this is happening now because women feel they have a voice,” she says. “And the great thing is they’re using it on such a big platform: social media.”

Twenty-five years after founding Australia’s first agency for curvy fashion models, Chelsea Bonner finds herself, and her company Bella (now expanded to manage models picked from that full spectrum of humanity) at what she hopes is a tipping point in history.

“The old rules have caused so much personal stress, especially for women,” she says. “Look at the damage, the pressure women are under to look a certain way, be a certain size. It puts the fear of God in us: ‘be this way, or you won’t belong’ or, ‘if you don’t change, you can’t be in my game’. It’s evil and it plays on our most basic human emotions and needs.”

Bonner sees the push to relax beauty standards as a liberating opportunity to replace them with “real achievements” and “true worth”.

The oldest model in Strateas Carlucci’s line up was 85.

Photo: Audrey Michael

Jess Quinn is on the same wavelength. “You know, this conversation we’re having to open up to different forms of beauty, there’s no specific endpoint,” she says. “I don’t think we’re all ever going to love every single aspect of our body. We’re not going to look in the mirror any day soon and say, ‘wow, that’s the best cellulite I’ve ever seen’. But it would be good, wouldn’t it, to reach a point somewhere near ‘body neutrality’, where we are just what we are, we’re not focused on beauty, or our exterior at all.”

This morning, as Bonner watches her wannabes finish their walking ordeal with a relieved smile, or a laugh as the judges banter about hopes and hobbies, not campaigns shot or catwalks booked, it feels like another small step has been taken on the road to Quinn’s utopian idea.

“There’s joy in the air,” Bonner says jokingly, but I’ve been to enough model castings for fashion’s more typical lissom, grim-faced young lovelies in the past to think, “Well yes, actually, there is.”

Melbourne Fashion Week runs until Sept 5. Finalists from the Bella Unsigned model call will appear in a free spring fashion show starting at 1pm on September 5 in the Bourke Street Mall. Body positivity activist and model Robyn Lawley will also walk in the travelling runway up to the State Library and down to Melbourne Town Hall.